Filmmaker Shirley Yumeng He’s latest work, The Other Side of the Mountain, was set in motion after she happened upon a salient image during a trip to China: a mountain where one side was lush with trees and the other side was a bare, rocky surface, seemingly forgotten after some construction. He’s film is a meditation on finding one’s way home to Chongqing and what’s left behind or forgotten in the midst of rapid urbanization, where decadence and abundance are found side by side. I had the opportunity to interview her about her film and creative processes recently, and I’m delighted to share our wide-ranging conversation, which took place over e-mail over the past few weeks.

Anqi Shen: I’d love to know what’s giving you energy right now in your artistic practice. Where in the world are you currently?

Shirley Yumeng He: I’m currently in Beijing, about to celebrate the Spring Festival with my family after 8 years being abroad! Right now, what’s giving me energy in my artistic practice is the process of reconnecting ç with people, places, and even parts of myself. Fresh out of grad school, I’ve taken a step back to spend time with my family in my hometown, a place I was away from for many years. This time has been both grounding and creatively rejuvenating, as I’m seeing familiar things — places, routines, relationships — in a new light. There’s also a lot of nostalgia since many have changed.

I’ve also recently come to recognize how important habitual practices are for me to generate creative energy. Maintaining simple daily rituals — morning writing, reading throughout the day, and finding a balance between solitude and social time, filmmaking and other hobbies — has been essential to my creative flow. Admittedly, this hasn’t always been easy with frequent moves and transitions, but anchoring myself in these routines has been key to sustaining my energy and staying connected to my work.

AS: That’s lovely. We share a hometown, but I’ve never been back in the winter or for a Spring Festival. It’s interesting that you bring up the place of ritual in your creative flow, which I was thinking about when watching your film, The Other Side of the Mountain. In it you present some simple and striking rituals: the washing of feet, the work and leisure of observing a place and its people, sketching, getting a haircut … The film also struck me as being very measured in its framing and sound design, and I thought this might be the result of returning to a space more than once — making a habit of seeing the same thing in different ways. I’m curious how you went about filming and editing this project and how the process affected the end result.

SYH: Thank you for your observation. I think while it was trying to touch on some historical background and societal changes at large, the film is grounded by these small gestures, the quiet, everyday rituals that often go unnoticed but carry so much meaning when you allow yourself to stay with them in time. Washing feet, getting a haircut, praying — these acts are simple, yet they become profound in their repetition. I was reading a piece on sonic space-making by Mack Hagood and he brought up the buddha machine. It reminded me of the faint sound of Buddhist chanting that always played from a small plastic sound box in my father’s office or my grandmother’s home. This sound, often overlooked as background noise, holds a quiet but significant presence in these household spaces. Similarly, the silent prayers I chose to end the film on feel like an anchor, tying together the domestic and societal, the individual and historical. These repetitions become a way to connect and endure, something to return to and hold onto in a changing world.

I was in Chongqing twice for two seperate production trips. The first trip was unstructured, with wandering as the primary goal. The second trip, six months later, was more deliberate as we returned to many of the same places we had previously explored. To be in a space that feels both foreign and slightly familiar is an exciting state for me. It stirs up a constant curiosity about my surroundings, tempered by a growing sense of direction and understanding. This process of returning, observing, and connecting is central to my practice. And field research allows me to engage deeply with a place, forming connections with those who inhabit it and discovering new layers while also recognizing the details that remain constant, like sounds or textures.

This has also influenced my approach to sound design. My goal was not to create the most realistic sonic representation but an impression of the space, one that merges different times and moments. The soundscape is less about what the place is and more about how it feels.

In the editing process, I spent a lot of time trying to balance how much to contextualize versus allowing space for interpretation. At one point, I thought the film needed a more overt narrative conflict, perhaps it could be the generational tension with my father since it had come up during production. But over time, I came to realize that the tension the film calls for is more abstract—between the private and the collective, memory and record—or even more simply, in the relationship between each shot and image.

Since this is a short film and not shot in a vérité style, I didn’t have an excess of footage to sift through. Certain scenes were non-negotiable, and there were individual images I couldn’t bear to leave out. After the rough cut, I shifted my approach to focus on the images themselves. In a somewhat old-school method, I printed out screenshots of each shot and laid them out to see all the ingredients of the film at once (here is a picture of them on my wall at one point). The visual relationships between the images in turn reshaped how I thought about editing and structuring the film. It became less about constructing a linear narrative and more about building a dialogue between the images themselves.

AS: I appreciate your generous response and your openness about parts of the production process. I was particularly struck by your intentions with the soundscape. It reminded me of the opening epigraph: “We do not live on soil; rather, we live in time.”

When I was watching The Other Side of the Mountain, and seeing the shots of Chongqing, I thought of the film Still Life (三峡好人) by Jia Zhangke. Have you seen it? Were you influenced by any artists or filmmakers in the making of this project and how it ‘feels’?

SYH: I’m glad to hear that you thought of Jia Zhangke’s Still Life, it was definitely on my mind while making this film — his way of framing transient landscapes and everyday gestures as both deeply personal and historically revealing has always resonated with me. I was also inspired by a lineage of films that embrace drifting observation, particularly those by Wim Wenders and Michelangelo Antonioni, where landscapes are not just settings but characters in themselves, holding the weight of time.

Walter Benjamin’s idea of the flâneur — the wandering observer who reads the city like a text—was also an influence. I think filmmaking, in many ways, mirrors this same kind of wandering. I’ve always wanted to make a film on this kind of embodied knowledge, how to get to “know” through our bodies, movements and perceptions in a space.

In a different sense, I was also influenced by the tactility of Chinese ink painting, where presence is just as much about the empty spaces as it is about the strokes. This way of seeing influenced the film’s framing and pacing — what remains unsaid or outside the frame can often carry as much weight as what is visible.

AS: You’ve alluded to this in a previous answer, but what was it like straddling the line between the personal and the societal in this film? Is this something that you’ve navigated with your past work as well?

SYH: Every journey is personal, but every road is shared. I’ve started to see the personal and the societal as intertwined rather than separate. The way we move through a city, the memories we attach to spaces, the habits and rituals that shape our days — these are deeply personal, yet they are all informed by larger forces: urban development, migration, erasure. Chongqing is a city in constant flux, where demolition and construction happen simultaneously. Walking through it, you sense an urgency to move forward, but also traces of what lingers. The personal stories in my film are not just personal, they are echoes of a collective experience of living in a place that is constantly changing.

And we experience history not as an abstract force but through small, seemingly inconsequential moments that are deeply personal. This has been a continuous thread in my work, an attempt to highlight the personal as a way through which history is felt and lived. In previous works like Fortune (2023) and Lacuna (2024, co-directed with Carlo Nasisse), similar to The Other Side of the Mountain, landscapes serve as the sites where the personal and societal intersect.

AS: When you mention ink painting, I think of those frames when your father is painting what he sees in front of him. In some senses, I see this film as a conversation between the two of you — two artists in search of a way home and a deeper understanding of how past and present are intertwined, how to see things in proportion and perspective. Are there any themes in the film that you’re looking to probe in future work? What are you most looking forward to in the year ahead?

SYH: I find myself drawn to ambiguous spaces, landscapes in flux — places where history is layered, where past and present are in constant negotiation. I am particularly interested in the emotional and psychological dimensions of urban transformation. How does the way we inhabit space reflect broader social conditions? How do erasure and displacement manifest on both a physical, collective, and personal level? These questions are central to my practice, as is my interest in the past lives of landscapes and their uncertain futures — shaped by climate change, urban development, and shifting social structures. Looking ahead, I am excited to expand my practice beyond documentary film and experiment with different forms of spatial storytelling. I am currently developing both a fiction film and an installation that delve into these themes, while continuing to observe and document urban landscapes as a filmmaker and flâneur in my travels.

The Other Side of the Mountain premiered at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) in November 2024 and will be screened at other festivals in the coming months. Information about future screenings can be found here.

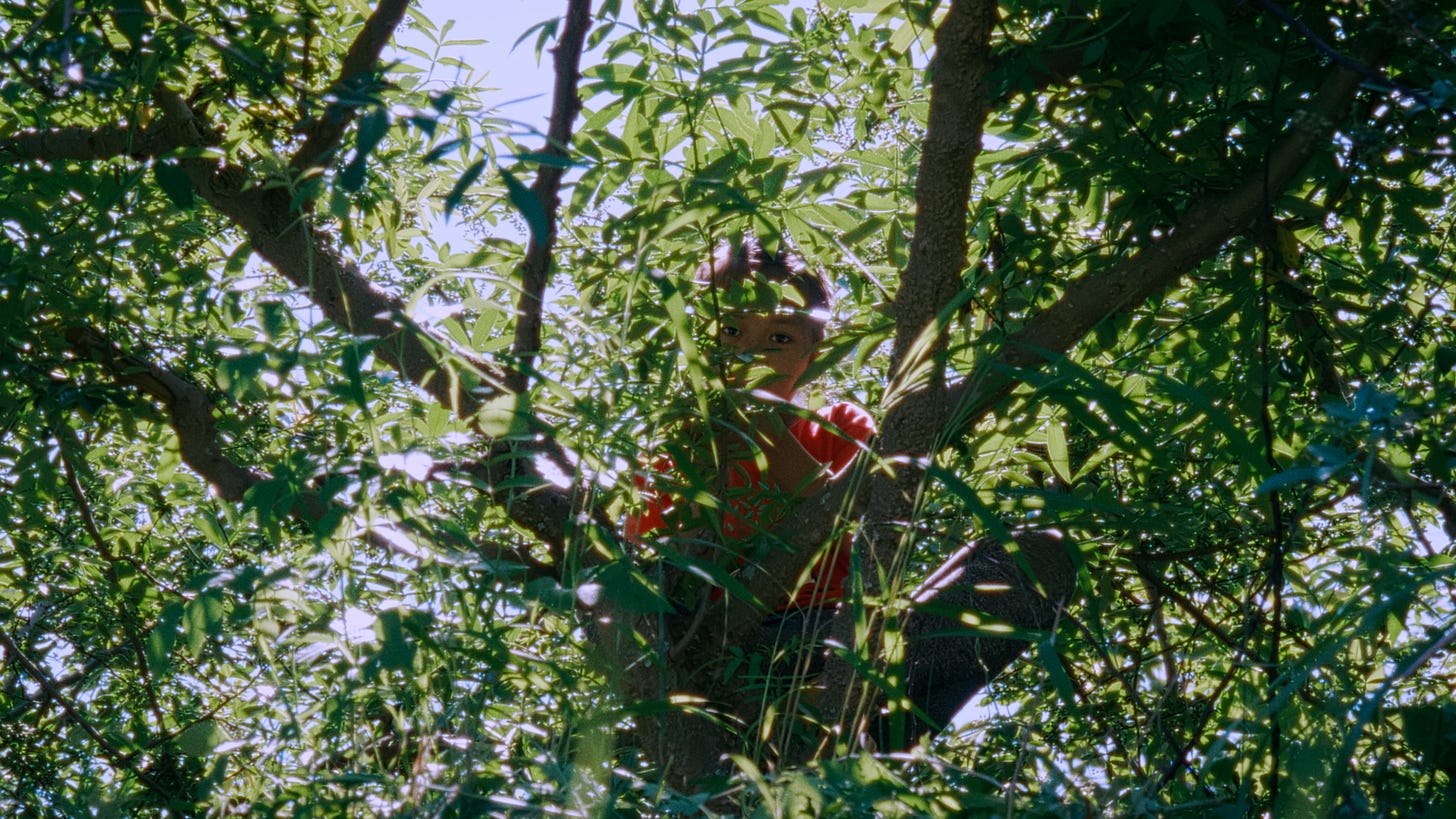

Stills from The Other Side of the Mountain courtesy of the filmmaker.